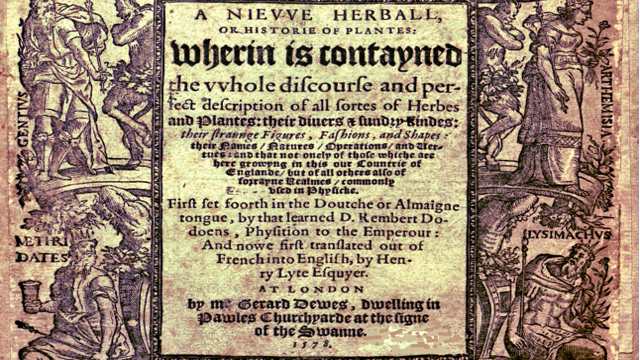

The intertwining realms of magic and science have long fascinated historians, particularly in the context of herbal medicine. In the past, herbals often contained occult elements, with plants classified according to their planetary or zodiacal properties.

A prime example is Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (1653), which included such classifications. However, as Enlightenment ideals spread across Europe, these superstitions gradually gave way to a more scientific approach to botany and medicine.

One compelling story from this transitional period is that of Elizabeth Blackwell, a pioneering herbalist and artist whose life was marked by loyalty, hardship, and remarkable resilience.

Born into a wealthy family in Aberdeen, Scotland, between 1707 and 1713, Elizabeth Blachrie’s life took a dramatic turn when she secretly married her second cousin, Alexander Blackwell, a physician with questionable credentials. Facing scrutiny and disputes over his qualifications, the couple fled to London in search of a fresh start. In London, Alexander ventured into the printing trade, working as a proofreader and eventually opening his own print shop in the Strand. However, the strict trade regulations of the time led to conflicts with powerful guilds, resulting in Alexander’s imprisonment for debt.

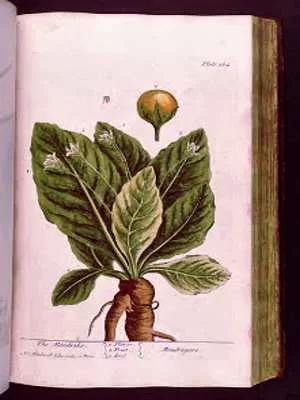

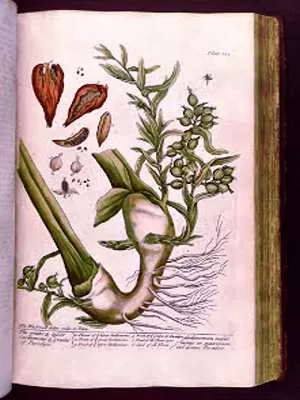

With her husband incarcerated, Elizabeth found herself in dire financial straits. Drawing on her artistic training from Aberdeen, she began creating exquisite botanical illustrations. Alexander, from his prison cell, contributed medicinal information to accompany her artwork. Their collaboration was a testament to their enduring bond, even in the face of adversity.

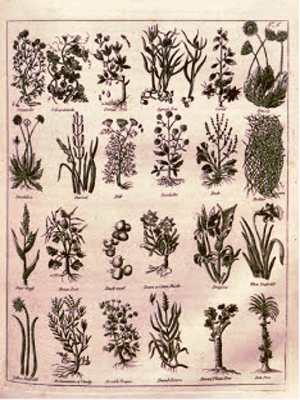

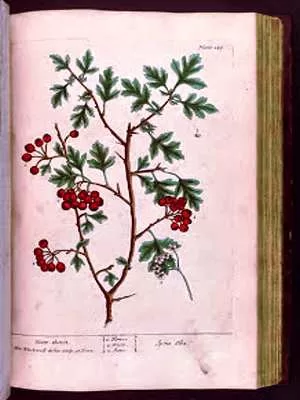

Elizabeth’s talent caught the attention of prominent figures in the medical community, including Sir Hans Sloane and Dr. Richard Mead, who encouraged her work. Gaining access to the Chelsea Physic Garden, Elizabeth meticulously illustrated plants from life, producing four plates a week. Over 125 weeks, she compiled her work into a groundbreaking herbal titled A Curious Herbal, which featured 500 detailed illustrations and descriptions of useful plants in medicine.

Published in 1737, the first volume of A Curious Herbal was a moderate success, providing enough income to secure Alexander’s release from prison. However, financial struggles persisted, leading to the eventual sale of the copyright. Despite this, the work was republished multiple times, including editions in 1739, 1751, and 1782, and even found its way to the continent.

Alexander Blackwell’s life continued to be tumultuous. After gaining the attention of James Brydges, Duke of Chandos, he was appointed to oversee improvements at the Duke’s estate but was dismissed under dubious circumstances. In 1742, he traveled to Sweden, leaving Elizabeth and their child behind in London. There, he attempted to pass himself off as a physician, attending to King Frederick, but faced accusations of quackery. His foray into agriculture also ended poorly, culminating in mismanagement of a model farm and further alienation from Swedish royalty.

Blackwell’s involvement in court intrigues ultimately led to his downfall. Accused of treason, he was sentenced to death. On August 9, 1747, just as Elizabeth was en route to join him, Alexander met his grim fate at the hands of the Swedish executioner. An apocryphal tale suggests that he mistakenly placed his head on the wrong side of the block, apologizing for his error, claiming it was the first time he had been beheaded.

After her husband’s execution, Elizabeth Blackwell seemingly vanished from historical records, with some accounts suggesting she may have worked as a midwife. The exact year of her death remains uncertain, but it is believed she passed away in 1758 and was buried at Chelsea Old Church, near her friend Sir Hans Sloane.

In the 1920s, playwright Constance Smedley stumbled upon Elizabeth’s story and was inspired to write a verse play titled The Curious Herbal (1922). The play depicted Elizabeth’s determination to gain access to the Physic Garden and her struggle against the misogynistic attitudes of the time, particularly in her interactions with the head gardener, Miller. Unfortunately, there are no records of the play being performed since the 1940s.

Elizabeth Blackwell’s legacy as an artist and herbalist endures, highlighting the significant contributions of women in the history of medicine. Her journey from privilege to poverty, and her unwavering loyalty to her husband, serves as a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by women in the 18th century. Through her artistry, she not only documented the botanical world but also carved a space for herself in a male-dominated field, leaving an indelible mark on the history of herbal medicine.