The history of the Starkie family in Lancashire is intertwined with the broader narrative of witchcraft and societal upheaval in 17th-century England. Nicholas Starkie of Cleworth is a descendant of a notable lineage that traces back to his grandfather, Laurence Starkie.

Laurence married Florence Atkinson from Skipton, and their son, Edmund, became the father of Nicholas. After Laurence’s death in 1547, Florence remarried Roger Nowell of Read, creating a complex family dynamic that would play a significant role in the events that followed.

Roger Nowell, a prominent figure in the region, had a son, also named Roger, who inherited the Read estate after his father’s death in 1591. Roger junior thrived in his position, becoming a magistrate and, in 1610, the High Sheriff of Lancashire.

His family connections were impressive; he had two great uncles who were distinguished Elizabethan divines—Alexander Nowell, Dean of St Paul’s in London, and Laurence Nowell, Dean of Lichfield. Additionally, Roger had second cousins who held significant positions, including Dr. William Whittaker, Master of St John’s College, Cambridge, and John Wolton, Bishop of Exeter. With such a pedigree, Roger Nowell’s Protestant credentials were impeccable, and his ambition was palpable.

When King James I ascended to the throne in 1603, the political landscape shifted dramatically. James was acutely aware of the dangers posed by witchcraft, particularly after a harrowing experience during his marriage to Anne of Denmark. In 1589, their return journey from Denmark was marred by violent storms, which led to accusations that witches were responsible. This incident prompted James to initiate the North Berwick Trials, resulting in the arrest of over a hundred suspected witches. Under torture, many confessed to being in league with the devil, revealing the extent of the hysteria surrounding witchcraft at the time.

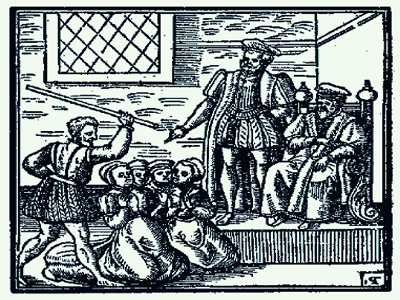

One of the most notorious cases from these trials was that of Agnes Sampson, who, after brutal torture, confessed to a plot involving over two hundred witches conspiring to kill the King. Her detailed account of a private conversation between James and Anne on their wedding night convinced the King of her guilt, leading to her execution. Similarly, Dr. Fian, another accused witch, faced horrific torture, including having his fingernails pulled out and being subjected to the “boot,” a device that crushed his limbs. His steadfast denial of guilt was interpreted as evidence of his deep-seated evil, culminating in his execution as well.

In 1597, King James published Daemonologie, a treatise that served as a handbook for witch-hunting and outlined the legal framework for dealing with accused witches. He argued that witches should be executed according to biblical law, specifically referencing Exodus 22:18, which states, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” This publication, along with changes to witchcraft laws in 1604 that increased the punishment from imprisonment to execution, set the stage for the witch hunts that would follow.

Roger Nowell, well-read and knowledgeable about the new laws, was positioned to act decisively when accusations of witchcraft arose in his jurisdiction. On March 30th, 1612, he was approached by Abraham Law of Halifax, who brought forth a teenage girl named Alizon Device, accusing her of witchcraft. This marked the beginning of a series of events that would lead to one of the most infamous witch trials in English history.

The Starkie family legacy, intertwined with the ambitions of Roger Nowell and the societal fears of witchcraft, illustrates the complex interplay of personal history and broader historical events. The witch hunts of 1612 were not merely a series of trials; they were a reflection of a society grappling with its identity in a time of religious and political turmoil. As we explore this dark chapter in history, it is essential to recognize the human stories behind the accusations and the tragic outcomes that ensued, reminding us of the dangers of fear and superstition in any era.