Having received a record number of AFI Award nominations, therefore standing at the apex of an unexpectedly strong year for Aussie film, and even garnering some Oscar buzz, David Michôd’s Animal Kingdom lays claim to being a must-see cinema event of 2010. That claim is baseless. Animal Kingdom is derivative, obvious, dingy, and soporific, attempting to dress its gratuitous filching from better movies, one-note, poorly detailed characters, and increasingly senseless story development and character actions, with endlessly portentous pseudo-ambient music and faux-meaningful voiceover reflections. With reasonable confidence, Animal Kingdom offers, in its first scene, the casually tragi-comic spectacle of teenaged protagonist Joshua “J” Cody (James Frecheville) calmly awaiting and greeting the arrival of paramedics to attend to his mother, who’s just OD’d, whilst a TV game show blares away in the corner, paid fleeting attention by J as awaits fate.

The subsequent film, however, plays out as an over-aestheticised version of the sleaze-mongering true-crime series Underbelly, in telling a story thinly fictionalised out of the lives of various headline-making Melbourne crime families, equipped not with fortunes and endless ranks of dedicated hoods, but operating out the plainest suburban bungalows, with the most unswervingly sub-plebeian of outlooks and lifestyles. J is adopted by his grandmother, Janine “Smurf” Cody (Jackie Weaver), matriarch for her collective of bad-boy sons, reputed for their misadventures with bank robbery and drug dealing, from which J’s mother was the lone, yet irreparably damaged, emigrant. Smurf is the beaming, enabling mother bear for this mob of terminal fuck-ups, whilst gang leader Barry “Baz” Brown (Joel Edgerton), a family friend and the captain of the criminal crew who seems to have been adopted into their number, is the supposedly becalming influence on dim, blonde husky pup Darren Cody (Luke Ford), semi-autistic psycho Andrew “Pope” Cody (Ben Mendelsohn), and twitchy, coke-snorting-and-selling Craig Cody (Sullivan Stapleton).

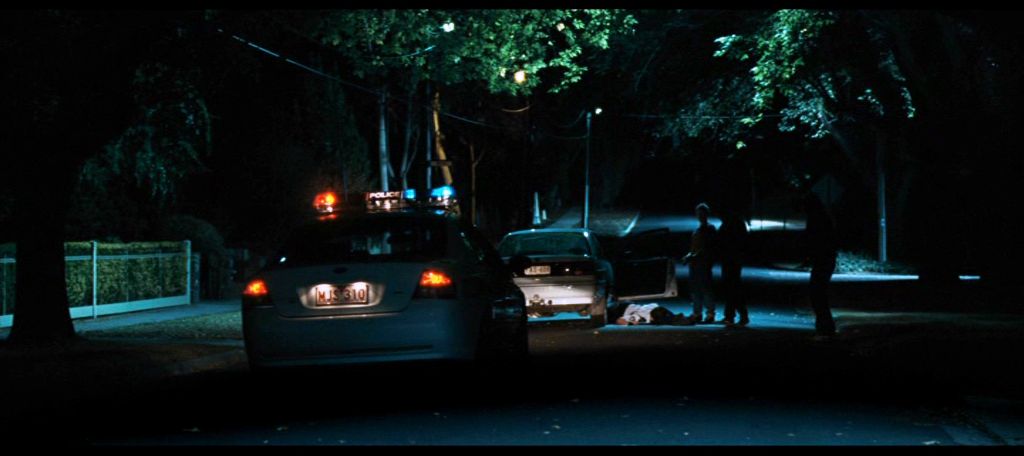

None of the above characters is developed in any more depth than the thumbnail descriptions I’ve given above, and J remains a cipher at the centre of the subsequent drama, knitting his brow and mumbling with all the expressive depth, emotional engagement, and inspired empathy of a cinder block. The attempts to ground the drama in an ironically normal, everyday kind of location and atmosphere add up to little because the social and extracurricular lives of the characters are poorly described. Everyone has a nickname, because that’s what gangsters have. Cheesy, queasy hints of incestuousness in the intimate kisses mother gives sons leads exactly nowhere except to lend the film low-rent hints of classical tragedy and psychosexual hype. The disparate personalities of the crime family are all rigorously obvious – you know the moment Pope enters the picture that he’s going to prove a handful in his infantile ruthlessness, and that Craig will inevitably die in a welter of drug-fuelled paranoia and desperation. Within seconds of delivering dialogue that confirms he wants to give up this sordid life of crime, Baz is “shockingly”, brutally dispatched by trigger-happy Armed Robbery Squad officers, in one of a string of assassinations they’re carrying out with impunity, making the local underworld understandably defensive. Without Baz, Pope’s loopy ideas of how to be an effective master criminal take over the whole enterprise. Feeling obligated to avenge his brother, he arranges the shotgun murder of two patrolmen, getting J to steal a car that is then used as bait to attract the victims. J is grilled by Leckie (Guy Pearce), a straight-arrow top cop who tries to offer J a safe path to opting out of this family fun if he becomes a friendly witness.

Michôd tries to prod the attention with twists and turns that are constantly predictable, but his script is that odd kind of beast where there’s nothing that’s immediately, obviously bad, with serviceably realistic dialogue, and yet cumulatively reveals itself to be barely competent. Almost nothing that happens in the film’ second half feels well-developed or believable. J hooks up, in circumstances that are poorly explained, with a girlfriend, Nicole (Laura Wheelwright), from a stable family but trailing ill-described maternal resentment, whose fondness for a little controlled substance abuse and mind-melting ignorance towards the clan of crims whose pictures she sees plastered all over the TV, does nothing to prevent her placing herself in menace’s way for the sake of the most dubious dramatic convenience. The overall thesis of the film, borne out via the stultifying obviousness of the title, is the notion that survival here is a matter for the fittest, and J evolves into a creature capable of lording over this jungle after receiving the requisite number of hard knocks. Yet his adaptation carries no impact because he’s such an uninspiring blank slate, and his final act of revenge – or is it culling the herd? – is the cheapest variety of resolution, a phoney-feeling punchline that makes practically no sense either in logic of behaviour or even simple criminal common sense.

The plot finally seems to be in danger of leading somewhere engaging when J’s imminent testimony sees him become a pawn between two camps of police, one charged with defending him, the other incorporating drug squad thugs eager to silence someone who knows their business. But even this proves to be little more than a tease, as the film refuses to condescend to any generic touches like action and excitement. The narrative lopes without pace or force towards its given end after some fiercely afunctional sequences in which J rehearses the spoiler testimony he wants to give to avoid Smurf’s wrath, and stretching out its running time by about ten minutes thanks to endless sequences of people walking in over-scored slow-motion. Amongst a raft of drably boilerplate acting school impressions of degeneracy, Pearce, sporting an amusingly anachronistic ‘70s cricketer moustache, claims acting honours, imbuing the flatly conceived Leckie with a down-to-earth gravitas and easy manner that belies his stodgy look. Weaver is competent, but her performance, which chiefly relies on the disparity between her cutesy-poo persona and the often coldly Machiavellian things she easily accedes to, has been absurdly over-rated. The bullet that finally puts Pope out of action also puts this pretentious yet utterly humdrum drivel out its misery.