The debut film of neophyte writer-director Blair Erickson, The Banshee Chapter is that rarest of modern cinematic beasts: a genuinely creepy horror film. Superficially, it seems to be another entry in the found-footage movie stakes. But actually Erickson uses the device sparingly, via pieces of footage the characters in the movie proper watch, or interpolated through the film as a whole as a narrative refrain, offering piecemeal glimpses of unholy experimentation and a legacy of evil that dogs the film’s unwitting characters. In fact The Banshee Chapter is a very classical horror film, evoking the Val Lewton method of horror by suggestion with all brief, snatched glimpses of things strange and chilling. Moreover, Erickson exploits some genuine and disturbing phenomena with rich and authentic folkloric power, particularly the real-life horror of the infamous CIA-backed MKUltra experiments which saw volunteers given doses of drugs, including LSD, in the hunt for behaviour-altering power: Ted Kaczynski, the future Unabomber, was one such volunteer. Placed in the mix as well are an equally eerie real-life phenomenon, numbers stations, enigmatic broadcasts from the far reaches of the Earth that can be filled with strange drones, number-reciting voices, Morse code and musical snatches, well-known to radio enthusiasts (and musicians, including Wilco and Boards of Canada, both of whom have included samples from real numbers stations in albums). Erickson’s cunning tale gathers together these fillips of modern paranoia into a story that condenses conceits from several disparate sources in the horror and sci-fi genres, but manages to feel skittishly original and manages to maintain tension to almost the end.

Anne Roland (Katia Winter) is the spunky, whip-smart young internet journalist who is haunted by the mysterious fate of her college pal and not-quite-boyfriend James Hirsch (Michael McMillian), who was writing a novel based on the MKUltra experiments. James went missing after taking a potent drug developed for the government program, sent to him by a source he only describes as “friends in Colorado.” As recorded by an alarmingly discontinuous video of the event taken by his friend Renny (Alex Gianopoulos), James was quickly visited by a paranoid conviction that something was coming to his house, whilst a strange broadcast began to sound on his radio. A shadow looming at the window is followed by shattering glass, and then a brief glimpse of James grotesquely transformed, with black eyes and bloodied mouth. Renny was interrogated by police who suspected he killed his friend, but then Renny went missing too. Anne sets about investigating, checking out James’ house in rural Nevada, where she finds some clues about where the drug might have come from, as well as a partly erased video tape that contains footage from an MKUltra project that involved the synthesis of the drug using samples from dead bodies, and the spectacles of terror and pity inspired in test subjects. Anne is creeped out by strange noises in James’ cabin. She talks to a radio expert, who might also be a former NSA member, who identifies the strange radio noise in the video as a numbers station whose broadcasts can normally only be picked up somewhere out in the Black Rock Desert’s wilds in the middle of the night. Only good things can happen doing that on your own, right?

Anne heads out to the desert fringe to listen for the broadcast and does pick it up, only to suspect something is stalking her in the dark. When she catches sight of a vague figure in the fringe of her torchlight, she hurriedly flees the site. Her editor Olivia (Vivian Nesbitt) helps fill in a missing piece of the puzzle when she suggests the missive to “friends in Colorado” might be a reference to a novel written by author Thomas Blackburn (Ted Levine), a burlesque on Hunter S. Thompson, although Ken Kesey was the actual noted counterculture writer who did participate in MKUltra. When Blackburn tells Anne over the phone that the title of his new novel is “Fuck Off,” she approaches him in a bar in the guise off an enthusiastic fan (giving Winter a nice little spot of acting within acting as Anne, who’s English, puts on an American accent), and seems to charm him sufficiently so that he invites her to his place to take the drug along with his friend, alt-cultural chemist wiz Callie (Jenny Gabrielle), who synthesised the same batch that James took. Blackburn soon enough reveals that he’s rumbled Anne’s secret identity, and fools her into thinking she’s taken a dose of the drug, whilst Callie, who really has taken it, falls into the same trembling, terrified state as James did, raving that something is approaching the house, and that “They want to wear us!” Something indeed seems to invade the house and knock out the lights before snatching Callie off into the night, with a brief glimpse of her face now similarly misshapen and gruesome.

The Banshee Chapter ingeniously builds drama around real things that coherently if abstrusely combine real-life tropes that reek of post-World War 2, Cold War-era atmosphere, laden with hints of totalitarian power, amoral experimentation for furthering the ends of that power, and technological ephemera that speaks of the grey zones in the modern world’s cohesion, the toxic fall-out of an age of super-science and super-states. There’s some similarity here to the paranoid, white noise-fixated otherworldliness of The Mothman Prophecies (2002), as well as that modern touchstone for all things based in covert flimflam and wingnut suspicion, The X-Files. Erickson cross-breeds this with familiar supernatural menaces that deserve comparison with M.R. James, and indeed the mixture of immediate and layered storytelling here comes close to James’ writing approach. The film makes overt reference to H.P. Lovecraft, as Blackburn recites the plot of From Beyond at a most inopportune time for Anne as she ventures into an abandoned house, not congenial to resting shredded nerves. This turns out to be the right reference point, however, as Anne comes to realise that the drug operates on the human mind in the same way that the tuning fork in the story is supposed to, turning it into a kind of chemical receiver and conduit that attracts…what? Beings from unseen planes of existence that really do want to “wear” us. The extended, increasingly intense periods of nothing happening and then sudden, side-swiping pay-offs, often in the fake footage sections, is reminiscent of Paranormal Activity. But the film’s ability to sustain similar tension in more traditional sequences suggests the influence of Ti West, rendered a touch less preciously than that tyro’s work, but also lacking his refined touch with actors and dialogue. Elements of the finale, particularly the unknown thing beating mercilessly on the door, recall no less a horror film than Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), where that director recalled some of the lessons he’d learnt from his mentor Lewton.

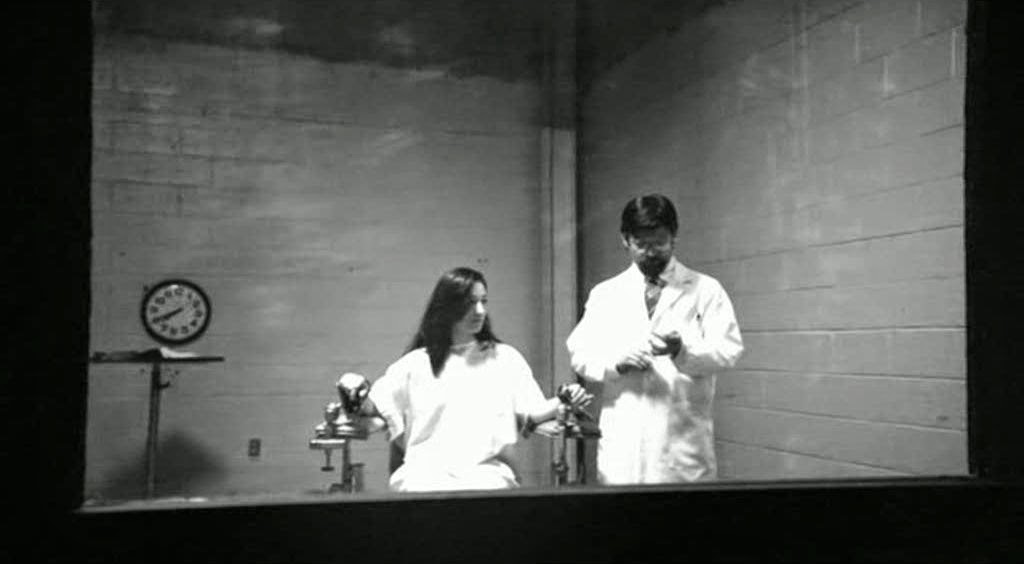

Thus Erickson is perfectly able to justify his unseen threats via a low budget by eliding them nimbly, building tremendous tension in some extended stare-at-the-screen found-footage patches and more traditional forays into old dark houses and abandoned military bases. The old taped fragments of the MKUltra experiments depict apparently dead bodies suddenly grabbing doctors and strapped, dosed patients in isolation chambers somehow escaping their bonds and pounding on two-way glass in mortal terror. Sometimes Erickson does lapse into a gauche theatricality with some of the punchlines to his expert tension building, and what The Banshee Chapter ultimately lacks is a proper, methodical approach to its dramatic exposition. Apart from some early refrains recalling Anne and James’ collegian days and her signalled regret at turning down his romantic overtures, the film’s time for characterisation is pretty scant. Which is a pity, because a feeling of blasted, haunted romanticism lurks within the material. Anne is driven by pain associated not just with the loss of a great pal and intellectual soul-mate but also of the openness of young adulthood, whilst Blackburn is tormented by a connection to the ensuing horrors to a degree he doesn’t seem aware of. Anne is an appreciably determined heroine, perhaps a little too much so, because the film’s urgent, tormented last hour that sees circumstances forcing her and Blackburn to do what any sane person would least like to do in such a predicament, might have had more impact if the characters were just a little more rattled by their situation. But Anne ploughs forthrightly in and Blackburn’s who-gives-a-shit attitude carries him in her wake.

The film doesn’t really live up to the realistic menace invoked by the MKUltra experiments either, which are used chiefly to give the film a crackle of verisimilitude, whilst the narrative moves into some familiar settings for terror-mongering, like a deserted old government research station filled with creepy medical equipment and tanks full of weird shit. Levine’s faux-Thompson is an unusual and inspired protagonist for a horror movie, and Levine’s performance is a great reminder of what an unusual, physically imposing, charismatic actor he can be. Blackburn’s presence offers ripe opportunities to coalesce Thompson’s famously scabrous worldview with events worthy of his famous catchphrase, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro,” and explore the real, semi-subterranean link between the MKUltra experiments and the burgeoning of the counterculture, which annexed and repurposed its wares and assumptions. Certainly the film’s narrative cleverly literalises the psychedelic culture’s idealisation of reality-shifting and drug use as a tool of contact with higher powers, and takes it a step further in making it prove to be a very bad trip indeed. But Blackburn never takes on much depth, a last minute revelation about his connection to the experiment adds very little to what’s already been guessed, and his part in the film remains a sketch for a better version.

Whilst the film mostly obeys the Lewtonian principles it sets out to honour with rigour, with the emanation stalking Anne only ever seen in the most vague and swift of manners, it could be argued that the inclusion of the found-footage conceit violates a basic rule of Lewton’s template, which was based around creating a dissonance between viewer and film that implied the untrustworthiness of the film as a record of the characters’ fears: the Lewton style was carefully subjective where the found-footage gimmick affects objectivity. And this in turn hurts the film’s thematic engagement with a porous sense of reality created by mind-altering experiments. The compressed, same-night rush of action in the film’s second half both helps Erickson sustain his nightmarish tone but also retards his opportunities to make deeper incisions into both the drama he’s created and the themes he’s pursuing. He’s put a lot of effort into making his film scary but not enough into realising its potential substance. Erickson also gets a bit too cute and familiar in the coda with an “unexpected” resurgence of the seemingly defeated dark force, which is by now so regulation that to do anything else would seem revolutionary. But it’s no sin that Erickson wanted to make an effective horror film first and foremost, which he’s certainly achieved. The climax is a terrific piece of extended menace in the abandoned facility, which bears traces, ominously, of having been hurriedly evacuated and left to whatever godforsaken entity now uses it as a hive. Erickson manages to whip a frenzy of alarm whilst still keeping his evil menace off screen, and the rush of action hurls Anne through states alternately distraught, fearsome, and desolate. Winter’s strength is a major pleasure here. For all its faults, hesitations, and final impression of subtle but definite let-down, The Banshee Chapter is still a fun ride.