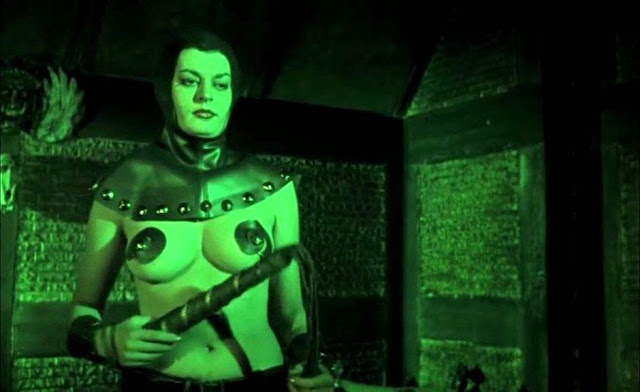

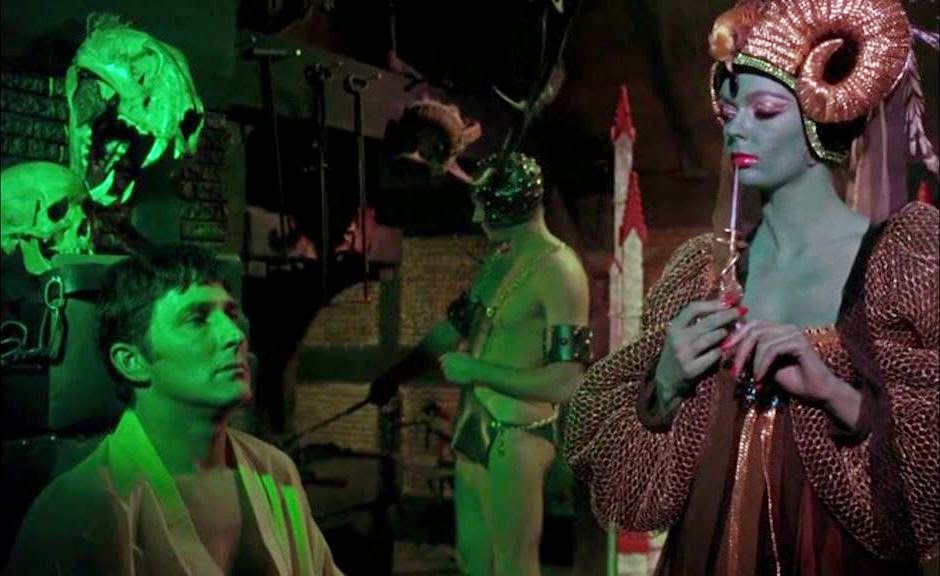

Although it brought together Boris Karloff, Christopher Lee, and Barbara Steele, shortly before Karloff’s death and at the cusp of Steele’s career wane, Curse of the Crimson Altar can hardly live up to the expectations such a confluence of horror movie icons creates. Smug antiquarian Robert Manning (Mark Eden) travels to the rural English town of Greymarsh where his family has roots, in search of his brother Peter (Denys Peek). The privileged viewer already knows what’s become of Peter, because a prologue has shown him selling his soul to Satan at a ritual sacrifice overseen by blue-skinned witch Lavinia (Steele), sealing his deal by plunging a knife into the heart of a victim. Lavinia was put to death by burning three hundred or so years earlier, but still seems to be haunting the dreams of anyone who stays at Craxted Lodge, a country manse owned by descendant Morley (Lee). The early scenes of Crimson Altar promise prime late-’60s disreputability, and fans of prime camp can get themselves into a serious lather at the opening ritual, which features a hooded, nipple-ornamented dominatrix (Nita Lorraine) mercilessly whipping some trussed blonde, and a stag-helmeted, G-string clad muscle man (Nicholas Head) beating hot steel and branding Peter as member of the Satanic club. Steele watches and directs, clad in ram’s-horn headdress and feathers, body painted blue with vivid red lips, a perfervid fetish totem climbed straight off a DC comic page, or Vladimir Tretchikoff’s Chinese Girl turned feral priestess.

Robert’s subsequent arrival in Greymarsh immediately offers more earthbound but equally sensationalist thrills. Robert leaps to the rescue of a half-naked woman being chased down by goons in cars bent on pack-rape, only for this to prove only a nasty party game, because the Lodge is hosting a decadent upper-crust bohemian rave where perversion and licentiousness are the currency of the night. The idea behind this scene, that the normally staid inhabitants of Greymarsh indulge a night of hedonistic delights before celebrating the death of their scapegoat, is intriguing. But instead of portending a descent into lovely depravity, all this saucy stuff instead proves mere modish ornamentation on a slack narrative that soon slows to a dawdle, with subplots left dangling and hope of even the most basic thrills dashed. The plot, possibly filched from a H.P. Lovecraft story and close enough to several other then-recent likenesses including John Moxey’s City of the Dead (1960), Roger Corman’s The Haunted Palace (1963), and Michael Reeves’ The She-Beast (1965), meanders as it duly sets up red herrings, particularly Karloff’s aged, wheelchair-bound Professor Marsh, brandy enthusiast and scholar of occultism and medieval torture, and his tall, mute chauffeur (Michael Warren), who may or may not have tried to blow Robert’s head off whilst pheasant shooting. Lee plays a host so avuncular he must be hiding something. Meanwhile Robert romances Morley’s niece Eve (Virginia Wetherell) with all the charm of a ferret in a tar puddle. Invited to stay with the Morleys in Craxted, Robert is beset by dreams where he sees Lavinia and her cadre of demonic helpmates, who attempt to force him to sign his name in the devil’s ledger. Soon it emerges that the Mannings’ forefather was the judge who had Lavinia killed, and her shade seems to be operating through some flesh-and-blood avatar to complete her revenge by claiming their descendents’ souls. Michael Gough is thrown into the mix as a frightened, batty servant who tries to warn Robert.

The direction by veteran filmmaker Vernon Sewell is solid but also rather mercenary, going for gold early on with all that kinkiness but undermining the script’s half-hearted attempts to create some narrative ambiguity. As the film rolls into its third act, screenwriters Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln seem to be leaning towards demystifying their plot, as Robert discovers a hidden chamber that’s been carefully dressed to look disused, and shots later offer the villain working his diabolism with satanic helpmates who are actually just costumes on frames, suggesting all the black magic is just the by-product of a sick mind. But the film’s shoddy structuring, including the declarative opening and very finale, foils this. Sewell’s career stretched back to the 1930s, and he had made several light horror and eerie films, most of which were variations on the same basic story, in which a young couple buys a haunted property, including the solid and modest Ghost Ship (1952). As horror became more popular in the ‘60s and halfway competent genre smiths were needed, Sewell branched out and made The Blood Beast Terror (1967), this, and 1971’s Burke and Hare before his career ended. The film’s chief pleasure is the photography by John Coquillon, who would soon become Sam Peckinpah’s preferred cinematographer: his palettes blend and balance autumnal mustiness with the saturated velvety interiors around the location (actually W.S. Gilbert’s house, the wonderfully named Grim’s Dyke). The night shots are expertly lit and atmospheric in shades of tallowy light and chiaroscuro dark, particularly when the revellers recreate Lavinia’s burning in a morbidly ecstatic parade through the dark trees on Morley’s estate, and later when Robert snoops through a graveyard in search of a clue. In such moments, Crimson Altar at least looks like a great British horror film. As Sewell tries to make his film hip with psychedelic flourishes, Coquillon obliges with dream and torture sequences drenched in violently bright colours, and kaleidoscope effects superimposed in for trippy textures or carving shots into delirious fragments.

Crimson Altar was made by Tigon, an upstart low-budget company that tried to wriggle into the British horror market like Milton Subotsky’s Amicus, and it gave a start to one major if doomed directing talent, Michael Reeves: notably, Karloff and Coqullion had worked on Reeves’ The Sorcerers the year before. Steele, in her first role since making her last major Italian film, the daftly arty An Angel for Satan (1966), is given absolutely nothing to do here except sit around and look weirdly beautiful. If regarded as a kind of photographic spread rather than movie, with Steele called upon to incarnate the ideal of erotic stygian femininity, Crimson Altar presents Steele at the peak of her iconic power in horror cinema. Sadly, at no point does she get to interact with Lee or Karloff. The film’s final twist reveals that Lavinia had taken possession of Morley, and the witch’s shade cackles down at her tormentors as the Lodge burns down around her. The intimations of gender subversion and sexual confusion lying behind Lee’s seemingly schismatic, weak-willed efforts to be evil, once again could have provided a more adventurous director with vast realms of exploitable weirdness. At least the climax offers the sight of Karloff managing to rise from his chair long enough to perform a little heroism, and in spite of his fragile health the actor still displays a gleeful theatrical ability to enliven proceedings, whereas Lee seems utterly without recourse. Crimson Altar is brief and competent enough to be a painless and even modestly profitable viewing for horror fans, especially if viewed as a flow of fragmented but individually appreciable elements. But what a disappointment it is as a whole.