A team of historians discovered a remarkable map drawn on a camel’s hide in 1929.

The paper was produced in 1513 by Piri Reis, a well-known admiral of the Turkish fleet in the sixteenth century, according to research that established its authenticity.

He was a cartographer at heart. He had exclusive access to the Imperial Library of Constantinople due to his high status within the Turkish Navy.

In a series of comments on the map, the Turkish admiral acknowledges that he assembled and duplicated the information from several source maps, some of which date back to the fourth century BC or earlier.

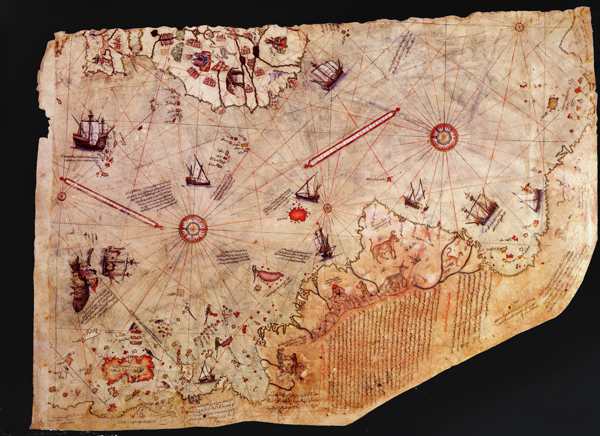

It measures 860 mm in height, 610 mm in width at the top (north), and 410 mm in width at the bottom (south), and was inked using nine distinct colors on parchment made from camel leather. Evidence of a missing parchment strip that would have likely represented the British Isles, Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland runs along the upper border of the map. Although the breadth of the map changes from north to south due to the natural curve of the skin, the eastern portion of the map has also been pulled away, creating a ragged edge. Several ships, the majority of which are Portuguese caravels, as well as legendary figures and parrots (called “tuti birds” and shown on the island of the Antilles) are used to represent it. On the map, 117 place names are displayed, the majority of which are recognizable and characteristic of late medieval portolan charts.

Portolans, based on the use of the magnetic compass and dead reckoning to compute longitude, were established in the late Middle Ages as mariners’ maps of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic coastlines of Europe. These maps were updated when new information was discovered as European nations started to explore the rest of the world. The portion of Piri Re’is’s 1513 map that has survived features a network of lines extending from five circular wind or compass rose patterns. These so-called rhumb lines display different compass directions and the direction of the prevailing winds.

The newly discovered New World is typically shown on this type of map at a larger size than the Old World. As a result, numerous coastal features are moved farther north and south than their true latitudes. The fact that the portolan chart contains seventeen compass roses indicates that the original map once showed the whole planet. The now-lost portions would have contained the last twelve.

Additionally, the map has thirty legends, 29 of which are in Turkish and 1 of which is Arabic and which identifies and dates the map’s creator. Turkish folklore provides information on the people, animals, minerals, and other wonders of the New World. Piri writes over South America in the Turkish mythology citing his sources, “This section covers the manner in which this map was made. In our day, there was no such map. Its creator and originator is your obedient servant. Twenty maps and charts serve as its primary foundation, one of which was created during the reign of Alexander the Great and is known to Arabs as Caferiye.

This map was created after comparison with eight other Caferiye maps, an Arab map of India and China, and a map of the western area made by Christopher Columbus, proving that it is just as accurate and dependable. By citing Columbus as the source for the map of the “western land” (i.e., the Americas), Piri further implies that it was not included on the earlier Caferiye maps. Most bad archaeologists do not quote Piri on this point, but he expressly disputes that it is a copy of an ancient map. Only Hapgood and his supporters see merit in the following assertion: Hapgood thought Piri had mixed Antarctica and South America on the wrong maps. He could only explain why Piri’s map was inaccurate in showing these continents.

Hispaniola was one of the locations Columbus had wanted to reach on his first trip; the form and orientation of the island are similar to those of Cipango (Japan) on portolans. He actually thought he had arrived at Cipango until, during his maiden journey, he found Hispaniola. Cuba is similarly depicted as being a part of the mainland since Columbus thought it was a large cape jutting east from Asia. In fact, Columbus would have been shocked to find that he had discovered a new continent because he thought “New Spain” was a part of Asia until his very last day. The placenames Piri noted in this part of the mainland come from Columbus’ second expedition and unmistakably identify the country as Cuba. These details confirm Piri’s claim that he replicated a map by Christopher Columbus by showing how closely related the map is to him.

It is claimed

Retired Captain Arlington Humphrey Mallery initially suggested that the Antarctic continent be included on a map in 1956. He was an amateur archaeologist who thought that the Celts, Vikings, and other Old World peoples had widely colonized North America and had accurate maps that had been lost to succeeding eras. It’s telling that Mallery used the word “decipher” to describe how he examined and pieced together what he thought the maps from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries showed. He believed that a single map was created by combining a number of separate maps, but that the subsequent copyists were unaware that their sources had various sizes, projections, and places of origin. Because of this, it was required to rearrange various portions of a single map in order to comprehend what the originals suggested.

William Hapgood

Strangely, Mallery was able to persuade a few others to support his reconstructions, including a number of officials from the US Navy Hydrographic Office. Charles Hapgood (1904–1982), a history of science instructor, also had a profound impact on him after reading a tape of a radio interview on Mallery’s interpretation of the Piri Re’is map. In the 1950s, Hapgood came up with his theory of what he called earth crustal displacement.

This theory holds that the earth’s crust is loosely attached to the underlying mantle and that it periodically slides across it, wreaking havoc on the entire planet. The accumulation of ice at the poles, which makes the crust top-heavy and causes it to migrate towards the equator by centrifugal force, is one of the reasons for these displacements. The theoretical physicist was so moved by his correspondence with Albert Einstein (1879–1955) that he contributed a foreword to Hapgood’s 1958 book, Earth’s Shifting Crust. The three maps mentioned on this website are among those that Hapgood claimed depicted Antarctica more than three centuries before it was officially discovered in the nineteenth century. He was the first to attract greater public attention to these maps. Hapgood contrasted Piri’s map with an azimuthal equidistant projection of the world centered at Cairo using aerial pictures obtained by the US Air Force.

Hapgood claimed that the original source maps, which he thought came from an early exploration of Antarctica when it was free of ice, were quite precise. He further reasoned that any discrepancy between the Piri Re’is map and contemporary maps was the consequence of Piri’s transcription faults. Starting from this point, it made little difference to Hapgood whether he used a Mallery-inspired technique to “correct errors” on Piri’s map by changing the scales between coastal stretches, redrew any coastline that was “missing,” or changed the orientation of landmasses.

Hapgood discovered that it was necessary to redraft the map using four distinct grids, two of which are parallel but offset by a few degrees and drawn on various scales; a third must be rotated clockwise nearly 79 degrees from these two; and a fourth is rotated counterclockwise nearly 40 degrees and drawn on roughly half the scale of the main grid. Hapgood discovered five distinct equators using this technique. The need to disregard the place names that cover the map will only make things worse. The placenames Piri provides correspond to those shown on other early sixteenth-century maps, many of which are still in use today.

Charles Hapgood and Erich von Däniken

Because of his convoluted reasoning and unconventional findings, Hapgood’s views did not get much attention when they were initially published. However, a number of writers, most notably Erich von Däniken, helped to popularize them. He simply reiterated Hapgood’s claim that Piri’s map shows an ice-free Antarctica as if it were established fact and suggested that the map could only have been created by extraterrestrials, either at a time when Antarctica was actually free of ice or because their technology revealed the underlying surface. Piri subsequently reproduced these precise maps, making multiple intermediate copies along the way that had flaws, inaccuracies, and uncertainties. Von Däniken also believed that the alleged lengthening of South America was due to satellite photography rather than the combining of four independent maps at various sizes.

The location designations on the southern landmass show that Piri considered the widely accepted notion of a southern continent. The idea was initially put out by classical Greek geographers, and it was later confirmed by Portuguese explorers traveling down South America’s east coast (some of whom may have made it as far as the Antarctic Peninsula). Even yet, the southern land Piri depicted has little resemblance to the Antarctic shore, ice-free or otherwise. The only similarity between them is their location south of the Atlantic Ocean and their primarily east-west coastlines.

Gerhard Kremer (Gerhardus Mercator, 1512–1594)’s reasoning for displaying a southern continent serves as an example of the influence of this notion. According to his world map, which was published in 1569, the land masses of the northern hemisphere must be balanced “under the Antarctic Pole [by] a continent so great that with the southern parts of Asia, the new India, or America, [it] should be a weight equal to the other lands.” This perspective, which originated with Classical geographers, helps to explain why so many cartographers in the sixteenth century were confident enough to depict the southern mainland even in the absence of any supporting data from seafarers.